The Invasion of North Africa, a Fortress Returns...

U.S. troops climb into landing craft , manned by Canadians, from the liner

Reina Del Pacifico during Operation 'Torch', Allied landings in N. Africa,

November 1942. Photo - Lt. F. A. Hudson, RN photographer, IWM

Introduction:

During World War II Ernie Pyle wrote stories that captured the attention of many North Americans. He travelled to some of the same places that would have been familiar to Canadians in Combined Operations. My father travelled to the shores of North Africa, for example, in early November 1942, and made mention of Americans on board the troop liner that he and other Canadian crew members of landing crafts were travelling upon. There were, therefore, many instances of RCNVR crews transporting US troops to foreign shores during Operation Torch, as seen in the top and next photograph.

During World War II Ernie Pyle wrote stories that captured the attention of many North Americans. He travelled to some of the same places that would have been familiar to Canadians in Combined Operations. My father travelled to the shores of North Africa, for example, in early November 1942, and made mention of Americans on board the troop liner that he and other Canadian crew members of landing crafts were travelling upon. There were, therefore, many instances of RCNVR crews transporting US troops to foreign shores during Operation Torch, as seen in the top and next photograph.

American troops landing on the beach at Arzeu, near Oran, from a landing

craft (manned by Canadians), some of them are carrying boxes of supplies.

Photo - A12649, Lt. F. A. Hudson, Imperial War Museum (IWM)

Background information from the memoirs of Doug Harrison, RCNVR/Combined Operations:

I became an A/B Seaman (Able-bodied) on this trip and passed my exams classed very good....

We had American soldiers aboard and an Italian in our mess who had been a cook before the war. He drew our daily rations and prepared the meal (dinner) and had it cooked in the ship’s galley. He had the ability to make a little food go a long way and saved us from starvation... One of the crew cheered us up and said, “Never mind, boys. There will be more food going back. There won’t be as many of us left after the invasion.” Cheerful fellow. However, we returned aboard another ship to England, the Reina Del Pacifico, a passenger liner, and we nicknamed the Derwentdale the H.M.S. Starvation.

In the convoy close to us was a converted merchant ship which was now an air craft carrier. They had a relatively short deck for taking off, and one day when they were practicing taking off and landing a Swordfish aircraft failed to get up enough speed and rolled off the stern and, along with the pilot, disappeared immediately. No effort was made to search, we just kept on.

On November 8, 1942 the Derwentdale dropped anchor off Arzew in North Africa and different ships were distributed at different intervals along the vast coast. My LCM had the leading officer aboard, another seaman besides me, along with a stoker and Coxswain. At around midnight over the sides went the LCMs, ours with a bulldozer and heavy mesh wire, and about 500 feet from shore we ran aground. When morning came we were still there, as big as life and all alone, while everyone else was working like bees.

There was little or no resistance, only snipers, and I kept behind the bulldozer blade when they opened up at us. We were towed off eventually and landed in another spot, and once the bulldozer was unloaded the shuttle service began. For ‘ship to shore’ service we were loaded with five gallon jerry cans of gasoline. I worked 92 hours straight and I ate nothing except for some grapefruit juice I stole.

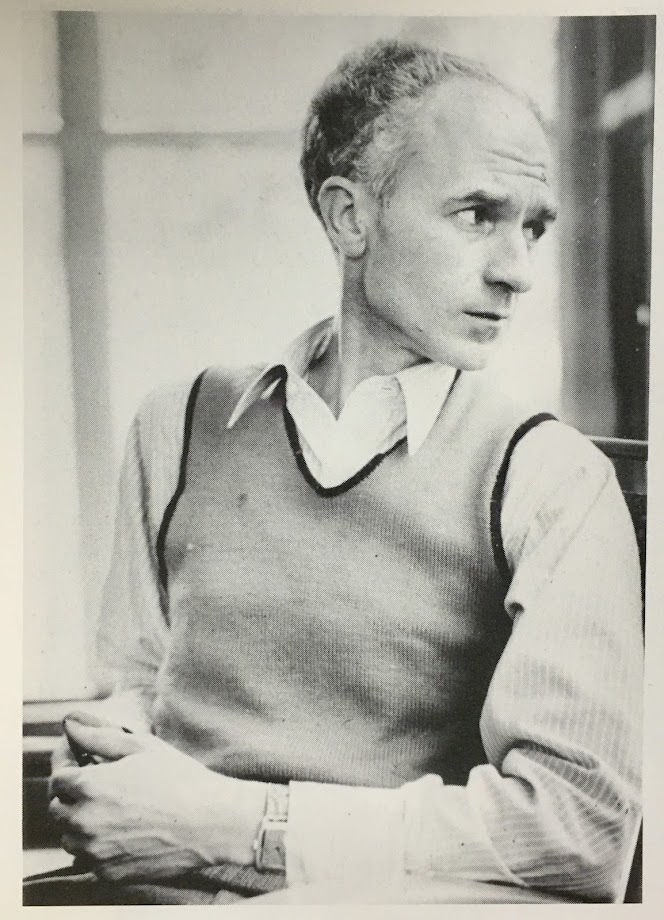

Doug Harrison (centre) watches as troops and ammunition come ashore

on LCAs at Arzeu in Algeria during Operation 'Torch', November 1942.

Photo credit - A12671 by Lt. F. A. Hudson, IWM

Our Coxswain was L/S Jack Dean of Toronto and our officer was Lt. McDonald RNR. After the 92 hours my officer said, “Well done. An excellent job, Harrison. Go to Reina Del Pacifico and rest.” But first the Americans brought in a half track (they found out snipers were in a train station) and shelled the building to the ground level. No more snipers.

Navy memoirs, "Dad, Well Done," pages 23 - 25

The following passages are found in Ernie Pyle's War: America's Eyewitness:

Operation Torch

On November 8, American invasion

forces landed in Morocco and Algeria.

Ernie followed two days later, sailing in a convoy

that reached Oran, Algeria, on November 23, 1942.

Operation TORCH was the first Allied assault

against Hitler from the West and the baptism

of American troops on the Atlantic side of the war.

The invasion had two military purposes:

to convert French North African troops heretofore

loyal to the collaborationist government in Vichy;

and to seize the key Tunisian ports of Tunis and

Bizerte in cooperation with the British Eighth Army,

fresh from its great victory at El Alamein in Libya...

TORCH would proceed in slow agony... by December hopes

for a painless success in North Africa had been dashed.

Both sides prepared for a protracted winter campaign.

Early in January 1943,

Ernie's column carried a deliciously exotic dateline:

"A Forward Airdrome in French North Africa."

(Censorship prevented him from naming it, though as he noted,

"the Germans obviously know where it is since they call on us frequently.")

It was the great American airfield at Biskra, the base for American

bombers... (it) was an oasis town called "the Garden of Allah."

It was hot under a brilliant sky during the day, cold at night...

The purple mass of the Atlas Mountains blocked the horizon.

Soldiers wore goggles against the blowing sand, which drifted around

the dry shrubs and penetrated the gears of the trucks and planes.

For the first time

he found himself in real danger.

Just three hours after he arrived,

German planes bombed the field.

In spare moments soldiers swung picks

and axes to deepen their slit trenches,

intermittently scanning the sky for parachutists.

After England and Oran, this was a sizable

step closer to war as Ernie had imagined it.

Just as he had done a dozen years earlier,

Ernie sat talking with privates and mechanics

and tracked the daily departure and arrival of planes.

And just as good stories had come to him at Bolling Field

on the Potomac, one came to him now at Biskra.

It was the story of an American bomber given up for lost.

From Ernie Pyle's War, pages 68 - 72

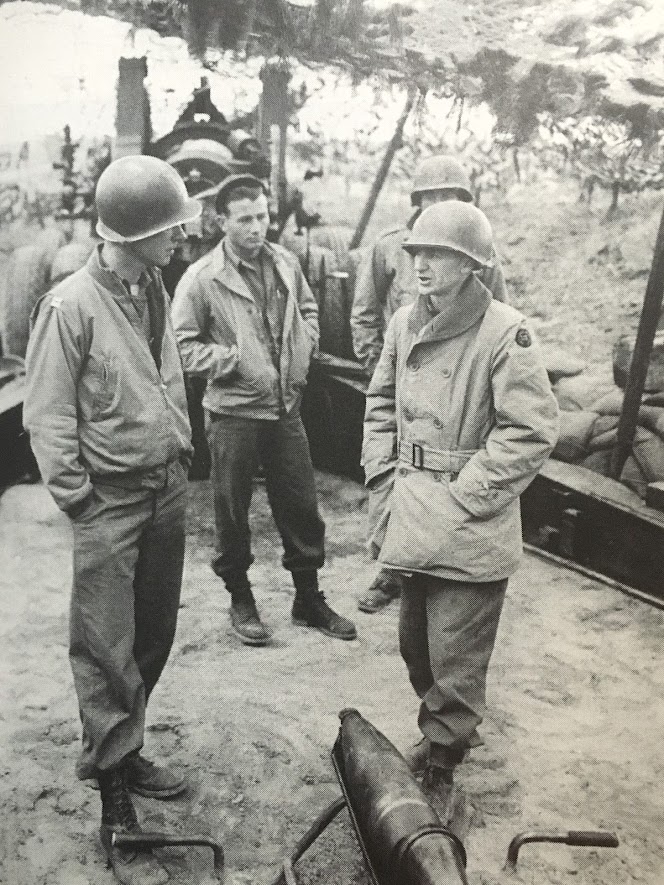

The 'roving reporter' was persistent to say the very least

Photo and caption above from Ernie Pyle's War, pages 120-121

ROVING REPORTER

A Forward Airdrome in French North Africa – (Jan. 22)

Ten men were in that plane.

The faces of his crew were grave, and nobody talked very loud.

The sunsets in the desert are truly things with souls.

And then an electric thing happened.

The second column followed two days later (below, as it appeared in The Pittsburgh Press, January 25, 1943), and the third two days after that. Columns poured out of the man.

ROVING REPORTER

The Thunderbird was forced to drop below the other Fortresses.

Our Lightning fighters, escorting the Fortresses, stuck by

The last fighter left the crippled Fortress about 40 miles from Tripoli.

The navigator came into the cockpit,

A Forward Airdrome in French North Africa – (Jan. 22)

You read the official communiqués a few days ago

about a devastating raid by our Flying Fortresses on

a huge German bomber airdrome near Tripoli.

What you didn’t read, at least in any detail,

is the story contained in these next three columns.

It was late afternoon at our desert airdrome.

It was late afternoon at our desert airdrome.

The sun was lazy, the air was warm, and a faint haze

of propeller dust hung over the field, giving it softness.

It was time for the planes to start coming back from

their mission, and one by one they did come –

big Flying Fortresses and fiery little Lightnings.

Nobody paid a great deal of attention,

for this returning is a daily routine thing.

Finally, they were all in – all, that is, except one.

Finally, they were all in – all, that is, except one.

Operations reported a Fortress missing. Returning pilots said

it had lagged behind and lost altitude just after leaving the target.

The last report said the Fortress

couldn’t stay in the air more than five minutes.

Hours had passed since then. So, it was gone.

Ten men were in that plane.

The day’s accomplishments had been great,

but the thought of 10 lost friends cast a pall over us.

We had already seen death that afternoon.

One of the returning Fortresses had released a red flare

over the field, and I had stood with others beneath the great plane

as they handed its dead pilot, head downward,

through the escape hatch onto a stretcher.

The faces of his crew were grave, and nobody talked very loud.

One man clutched a leather cap with blood on it.

The pilot’s hands were very white. Everybody knew the pilot.

He was so young, a couple of hours before.

The war came inside us then,

and we felt it deeply.

Half a dozen of us went to the high control tower.

We go there every evening, for two things –

to watch the sunset, and to get word on the progress

of the German bombers that frequently come

just after dusk to blast our airdrome.

The sunsets in the desert are truly things with souls.

The violence of their color is incredible.

They splatter the sky and the clouds with a surging beauty.

The mountains stand dark against the horizon, and palm trees

silhouette themselves dramatically against the fiery west.

As we stood on the tower looking down over this powerful scene,

As we stood on the tower looking down over this powerful scene,

the day began folding itself up. Fighter planes, which patrol the field all day,

were coming in. All the soldiers in the tent camps had finished supper.

That noiseless peace that sometimes comes just before dusk

hung over the airdrome. Men talked in low tones

about the dead pilot and the lost Fortress.

We thought we would wait a few minutes more

to see if the Germans were coming over.

And then an electric thing happened.

Far off in the dusk, a red flare shot into the sky.

It made an arc against the dark background of the mountains

and fell to the earth. It couldn’t be anything else. It had to be.

The ten dead men were coming home!

An officer yelled:

Where’s the flare gun? Gimme a green flare!

He ran to the edge of the tower, shouted, “Look out below!”

An officer yelled:

Where’s the flare gun? Gimme a green flare!

He ran to the edge of the tower, shouted, “Look out below!”

and fired a green rocket into the air. Then we saw the plane –

just a tiny black speck. It seemed almost on the ground,

it was so low, and in the first glance we could sense that

it was barely moving, barely staying in the air.

Crippled and alone, two hours behind all the rest,

it was dragging itself home.

I am a layman, and no longer of the fraternity that flies, but I can feel.

I am a layman, and no longer of the fraternity that flies, but I can feel.

And at that moment I felt something close to human love

for that faithful, battered machine, that far dark speck

struggling toward us with such pathetic slowness.

All of us stood tense,

All of us stood tense,

hardly remembering anyone else was there.

With our nervous systems,

we seemed to pull the plane toward us.

I suspect a photograph would have shown us

all leaning slightly to the left. Not one of us

thought the plane would ever make the field,

but on it came – so slowly that it was cruel to watch.

It reached the far end of the airdrome,

It reached the far end of the airdrome,

still holding its pathetic little altitude.

It skimmed over the tops of parked planes,

and kept on, actually reaching out –

it seemed to us – for the runway.

A few hundred yards more now.

Could it? Would it? Was it truly possible?

They cleared the last plane,

They cleared the last plane,

and they were over the runway.

They settled slowly. The wheels touched softly.

And as the plane rolled on down the runway,

the thousands of men around that vast field

suddenly realized that they were weak and that

they could hear their hearts pounding.

The last of the sunset died,

The last of the sunset died,

and the sky turned into blackness,

which would help the Germans if they

came on schedule with their bombs.

But nobody cared. Our 10 dead men

were miraculously back from the grave.

Photo Credit - Thunderbird

ROVING REPORTER

A Forward Airdrome in French North Africa – (Jan. 24)

The 10 men who brought their Flying Fortress home

from a raid on Tripoli, after they had been given up for lost,

will undoubtedly get decorations. Nothing quite like it

has happened before in this war. Here is the full story.

The Tripoli Airdrome was heavily defended,

The Tripoli Airdrome was heavily defended,

by both fighter planes and anti-aircraft guns.

Flying into that hailstorm, as one pilot said,

was like a mouse attacking a dozen cats.

The Thunderbird – for that was the name of this Fortress –

The Thunderbird – for that was the name of this Fortress –

was first hit just as it dropped its bomb load. One engine went out.

Then a few moments later, the other engine on the same side went.

When both engines go out on the same side, it is usually fatal.

And therein lies the difference of this feat from other

instances of bringing damaged bombers home.

The Thunderbird was forced to drop below the other Fortresses.

And the moment a Fortress drops down

or lags behind, German fighters are on it like vultures.

The boys don’t know how many Germans were in the air,

but they think there must have been 30.

Our Lightning fighters, escorting the Fortresses, stuck by

the Thunderbird and fought as long as they could, but

finally they had to leave or they wouldn’t

have had enough fuel to make it home.

The last fighter left the crippled Fortress about 40 miles from Tripoli.

Fortunately, the swarm of German fighters started home at the same time,

for their gas was low too.

The Thunderbird flew on another 20 miles.

The Thunderbird flew on another 20 miles.

Then a single German fighter appeared, and dived at them.

Its guns did great damage to the already-crippled plane, but

simply couldn’t knock it out of the air.

Finally, the fighter ran out of ammunition, and left.

Finally, the fighter ran out of ammunition, and left.

Our boys were alone now with their grave troubles.

Two engines were gone, most of the guns were out of commission,

and they were still more than 400 miles from home.

The radio was out. They were losing altitude, 500 feet a minute,

and now they were down to 2,000.

The pilot called up his crew and held a consultation.

The pilot called up his crew and held a consultation.

Did they want to jump? They all said they would ride the plane

as long as it was in the air. He decided to keep going.

The ship was completely out of trim,

The ship was completely out of trim,

cocked over at a terrible angle.

But they gradually got it trimmed

so that it stopped losing altitude.

By now, they were down to 900 feet, and a solid wall

By now, they were down to 900 feet, and a solid wall

of mountains ahead barred the way homeward.

They flew along parallel to those mountains for a long time,

but they were now miraculously gaining some altitude.

Finally, they got the thing to 1,500 feet.

The lowest pass is 1,600 feet, but they came across at 1,500.

The lowest pass is 1,600 feet, but they came across at 1,500.

Explain that if you can! Maybe it’s as the pilot said:

We didn’t come over the mountains, we came through them.

The copilot said:

We didn’t come over the mountains, we came through them.

The copilot said:

I was blowing on the windshield trying to push her along.

Once I almost wanted to reach a foot down and sort of

walk us along over the pass.

And the navigator said:

If I had been on the wingtip, I could have touched the ground

And the navigator said:

If I had been on the wingtip, I could have touched the ground

with my hand when we went through the pass.

The air currents were bad.

The air currents were bad.

One wing was cocked way down. It was hard to hold.

The pilots had a horrible fear that the low wing would

drop clear down and they roll over and go into a spin.

But they didn’t.

The navigator came into the cockpit,

and he and the pilots navigated the plane home.

Never for a second could they feel any real assurance of making it.

They were practically rigid, but they talked a blue streak all the time,

and cussed, as airmen do.

Everything seemed against them.

Everything seemed against them.

The gas consumption doubled,

squandering their precious supply.

To top off their misery,

they had a bad headwind.

The gas gauge

went down

and down.

At last, the navigator said

At last, the navigator said

they were only 40 miles from home, but those 40 miles

passed as though they were driving a horse and buggy.

Dusk, coming down on the sandy haze,

made the vast flat desert an indefinite thing.

One oasis looks exactly like another.

But they knew when they were near home.

Then they shot their red flare and waited

for the green flare from our control tower.

A minute later, it came –

the most beautiful sight

that crew has ever seen.

When the plane touched the ground,

When the plane touched the ground,

they cut the switches and let it roll. For it had no brakes.

At the end of the roll, the big Fortress veered off the side of the runway.

And then it climaxed its historic homecoming by spinning madly around

five times and then running backwards for 50 yards before it stopped.

When they checked the gas gauges, they found one tank dry

and the other down to 20 gallons.

Deep dusk enveloped the field.

Deep dusk enveloped the field.

Five more minutes and they never would have found it.

This weary, crippled Fortress had flown for the incredible time

of four and a half hours on one pair of motors.

Any pilot will tell you it’s impossible.

That night, I was with the pilot and some of the crew and

That night, I was with the pilot and some of the crew and

we drank a toast. One visitor raised his glass and said:

Here’s to your safe return.

But the pilot raised his own glass and said instead:

Here’s to a goddamned good airplane!

And the others of the crew raised their glasses and repeated:

Here’s to a goddamned good airplane!

And here is the climax.

Here’s to your safe return.

But the pilot raised his own glass and said instead:

Here’s to a goddamned good airplane!

And the others of the crew raised their glasses and repeated:

Here’s to a goddamned good airplane!

And here is the climax.

During the agonizing homeward crawl,

this one crippled plane shot down

the fantastic total of six German fighters.

These were officially confirmed.

The third column and much more related to Ernie Pyle can be found here - Roving Reporter, Ernie Pyle

Below are a few more passages from Ernie Pyle's War that tell us more about a war correspondent whose life was cut short while on assignment in the Pacific theatre of war.

The third column and much more related to Ernie Pyle can be found here - Roving Reporter, Ernie Pyle

Below are a few more passages from Ernie Pyle's War that tell us more about a war correspondent whose life was cut short while on assignment in the Pacific theatre of war.

Ernie's Self-Reliance

Though comfortable with the brass,

he spent most of his time with enlisted men and junior officers.

He dug slit trenches with them, ate meals with them,

kibbitzed with them, dove for cover with them

when German planes appeared overhead.

Some became friends whom Ernie saw repeatedly.

He observed G.I.s' feats of improvisation and followed suit.

He learned to brew a cup of coffee over a fist-sized hole

in the sand filled with gasoline. The Army's ubiquitous

gasoline cans became skillets and stewpots.

"I don't believe there's a thing in the world that

can't be made out of a five-gallon gasoline tin."

He learned that a mess kit could be kept clean with sand

and toilet paper, "the best dishrag I've ever found."

A quiet cheer welled in him as he performed small acts of self-reliance,

perhaps because he'd felt powerless in his personal life for so many months.

He slept on the ground, often waking in the morning

to find his bedroll dusted with snow.

Arriving at a farmyard command post one evening, Jack Thompson,

the Chicago Tribune's black-bearded correspondent,

watched Ernie prepare an overnight nest

for himself under a decrepit wooden wagon.

"From one corner of the farmyard he took a few sheets

of corrugated iron which he erected as a wind break.

Then with all his clothes on he crawled into his sack,

pulled his cap down tighter around his head,

snuggled down and grinned."

Ernie told readers he had laughed over the inordinate pleasure

he had taken in constructing his little shelter that night.

"It was the coziest place I'd slept in for a week.

It had two magnificent features -

the ground was dry, and the wind was cut off.

I was so pleased at finding such a wonderful place

that I could feel my general spirits go up

like an elevator."

Pages 79 - 80

"I Love the Infantry" - The Spring Campaign, 1943

On April 22, 1943, the Allies launched

their spring campaign against the Germans...

the Americans of II Corps were assigned to

take the lesser prize of Bizerte.

Ernie hooked up with the First Division... he felt

bonds of kinship tugging him toward these men,

"my old friends." But he perceived a change in them...

now they were soldiers. He heard the transformation in

"the casual and workshop manner in which they now talk

about killing. They have made the psychological transition

from the normal belief that taking human life is sinful,

over to a new professional outlook where killing is a craft.

To them now there is nothing morally wrong about killing.

In fact it is an admirable thing..."

The front-line soldier (at the tip of the spear)

"wants to kill individually or in vast numbers.

He wants to see the Germans overrun, mangled, butchered..."

It was a profound difference, shocking yet necessary.

"All the rest of us - you and me and even the thousands

of soldiers behind the lines in Africa - we want terribly,

yet only academically, for the war to get over.

The front line soldier wants it to be got over by the physical

process of his destroying enough Germans to end it.

He is truly at war. The rest of us,

no matter how hard we work, are not."

Pages 88 - 89

On Assignment in the Okinawa Campaign - April, 1945

Landings were set for April 16.

Ernie heard about a new tank destroyer being used on Ie;

he decided to get a look at it. He went ashore on the 17th,

talked with infantrymen during the afternoon and spent the night

near the beach in a Japanese ammunition-storage bunker.

In the morning he ate cold C-rations, then hitched a ride

with Colonel Joseph Coolidge, who was planning to cross

the island to find a new site for his regimental command post.

The fighting was inland, so the road from the beach was quiet.

At about ten o'clock, a Japanese Nambu machine gun chattered.

Pyle, Coolidge and the other men in the jeep

leaped out and jumped into a ditch along the road.

After a moment Ernie raised his head

and the machine gunner fired again,

hitting him in the left temple just

below the line of his helmet... (page 240)

Ernie Pyle's body lay alone

for a long time in the ditch

at the side of the road.

Men waited at a safe distance,

looking for a chance to pull the body away.

But the machine gunner, still hidden in the coral ridge,

sprayed the area whenever anyone moved.

The sun climbed high over the little Pacific island.

Finally, after four hours, a combat photographer

crawled out along the road, pushing his heavy

Speed Graphic camera ahead of him.

Reaching the body, he held up the

camera and snapped the shutter.

The lens captured a face at rest.

The only sign of violence was a thin stream

of blood running down the left cheek.

Otherwise he might have been sleeping... (page 1)

For a selection of forty wartime columns by Ernie Pyle, please click here.

For a copy of Ernie Pyle's War, please visit your nearest new/used book store with $10 - $15 or link to AbeBooks.com

Please click here to read Passages: Ernie Pyle's War - America's Eyewitness (Part 1)

Unattributed Photos GH

Unattributed Photos GH

No comments:

Post a Comment